Rīn (ऋण): Inheritance as Futures Already Bound

Some futures emerge through the anchors of obligation that precede aspiration

Rīn/ऋण is a Sanskrit-derived word, widely understood across Nepali, Hindi, and other South Asian languages. It is pronounced “Rin,” with the ‘n’ slightly curled back in the mouth.

It means debt, obligation, liability, what must be carried before choice. In this sense, it names the inheritances that arrive uninvited: claims that structure tomorrow in advance, liabilities that shape futures through obligation, rather than possibility.

Many accounts of the future begin with the language of choice: what worlds can be designed, what disruptions anticipated. But in many parts of South Asia, the future often begins elsewhere, with rīn, debts and obligations carried forward before imagination is even possible. To inherit here is to step into futures already bound.

The Futures We Don’t Choose

Much of South Asia lives inside coordinates already drawn: some nurturing, others constraining. Songs, rituals, and solidarities can travel across generations just as disputes, debts and exclusions do.

Inheritance stretches far beyond land or wealth. It is inscribed in caste location, in the bureaucracy of a surname, in obligations woven through kinship and ritual. It is also embedded in infrastructures and borders left behind by the ‘empire’, drainage lines, cadastral maps, and documents that continue to govern daily life. To inherit in this sense is to be positioned within liabilities that persist even as you move.

In Bihar, a young graduate applies for a government job. Her qualifications are strong, but the first line that matters is her surname. The name on the application positions her before she enters the room. It tells the examiner which caste location she comes from, what expectations to hold, and how seriously to take her claim. She cannot choose to set it aside. It is inherited, written into every form she fills.

To see inheritance is to notice how tomorrow is already being written, sometimes by continuities of care and sometimes by obligations that refuse to close.

If you think about it, inheritance anchors the starting point, but it does not anchor the ending. That ending is written and rewritten each time someone decides how to move within the coordinates they did not choose.

In our last Note, we spoke of Riyāz, the slow rehearsal of futures already in your hands. But another reality runs alongside it: the one where the script is handed to you after the casting is done, the sets are built, the story already decided. In those moments, futures work begins not in rehearsal, but in the refusal, re-routing, or rewriting of what was handed down.

What Inheritance Looks Like

Inheritance shows itself in everyday forms: cases that refuse to close, occupations that insist on repeating, landscapes that carry debts no one remembers incurring.

In northern Sri Lanka, families displaced during the war continue to inherit property disputes tied to missing persons, confiscated land, and incomplete resettlement. A generation later, children inherit the unresolved case files, the letters of claim and the unreturned deeds.

What’s being inherited here is absence, a future defined by the struggle to recover what was taken, and by the shadow of paperwork that never closes. Futures are scripted not by choice of livelihood but by the slow bureaucracy of return.

In the mid-hills of Nepal, small farming families inherit not only terraces of land but also the erosion left by earlier deforestation and road cutting. Each monsoon brings landslides that undo a season’s work. Children grow up learning where the soil will slip, which slopes cannot hold grain, and when to move animals before the rains.

What’s being inherited here is instability, a landscape altered by decisions made decades earlier, forcing each generation to live with soil that refuses to stay put. Futures here are measured in the careful management of loss.

In Dhaka’s garment districts, small workshops often pass from parent to child. But what is inherited is the precarity of subcontracting chains. A daughter stepping in may inherit long hours, wage arrears, and dependency on volatile export orders. What looks like succession is, in reality is the continuation of vulnerability. A future bound by the thin margins of global supply chains.

What’s being inherited here is precarity itself. A structural position within an economy that extracts labour but withholds stability. Futures here are written less in expansion than in survival, marked by the repetition of contracts that disappear as quickly as they arrive.

Inheritance takes many forms: legal, social, ecological. Each binds futures in advance, narrowing paths before choice arrives. To name them is to see how deeply tomorrow is structured by what was handed down.

The Right to Insert Yourself into Futures

Inheritance sets the coordinates, but it does not dictate the journey. To inherit is to step into conditions that already exist. These cannot be set aside at will. They must be carried. What matters is not only what is carried, but how one steps into it.

Futures work often treats imagination as a departure, a breaking free. But in South Asia, futures usually begin within what is already binding. Agency here lies less in escape than in insertion: acts of entering with intent, altering the trajectory from inside. To insert is to demand recognition in a system that sought to exclude you, or to re-enter a bureaucracy that had already marked your community as absent. At Lagori, we think of these as situated assertions made in the thickness of inheritance.

For insertion to matter at the scale of futures practice, it must be recognised as an infrastructural right. Doors must remain open across generations, fragments must count as live matter, and entanglement must be taken as ground, as actual foundations from where futures work begins. To design otherwise is to close off agency prematurely and to deny that inheritances outlast a single lifetime.

Insertion, understood this way, turns inheritance into a ground for agency. It shifts futures work away from abstraction and toward the everyday labour of stepping into what is already given, while refusing to let the given decide what comes next.

Inheritance as Infrastructure

If people inherit through names, debts, and disputes, systems inherit through the infrastructures that outlast their makers. Maps, canals, ledgers, and case files are architectures of repetition: embedding the decisions of one era into the daily life of another. Drainage lines dug for ports still dictate which neighbourhoods flood each monsoon.

To see inheritance this way is to see it less as legacy and more as architecture, built environments, and bureaucratic systems that actively reproduce the past in the present. They channel possibility into narrow paths, enforcing continuities that outlast law, policy, or even memory. Futures practice often treats infrastructure as a neutral backdrop to be repaired or redesigned. But in this region, infrastructures themselves are inheritances: they reproduce caste, debt, and displacement in ways that no individual can opt out of.

If riyāz shows how people persist through repetition, inheritance as infrastructure shows how systems persist through design. One is lived improvisation; the other institutional drag. Futures work cannot afford to ignore this second form. To imagine otherwise without recognising how infrastructures inherit is to mistake the stage for a blank floor when it is already crowded with props, boundaries, and walls built long before the script begins.

When Inheritance Becomes Extraction

Some inheritances hold people in place and others hollow them out. These are obligations that grow heavier with each generation. A loan passed down as if it were land, or a duty performed as if it were devotion. Here, inheritance is less about carrying forward and more about being compelled to repay, absorb, or endure.

This is the zone where inheritance becomes extraction: where futures are pre-spent, siphoned into servicing debts, identities, or liabilities never chosen. What looks like continuity from a distance is, up close, a mechanism for keeping lives in place so that value can be pulled elsewhere.

Extraction hides by disguising itself as continuity. Debt becomes family duty. Occupation becomes destiny. Refusal is framed as dishonour. By blurring the line between respect and compliance, systems make it harder to see where obligation ends and extraction begins.

The politics here matter. Extraction through inheritance is structural. Institutions stabilise themselves by designing the continuity of obligation. Debt is rarely extinguished; it is rolled over, refinanced, passed from agrarian credit to IMF schedules. Registries, whether land records or biometric databases, lock people into fixed categories where refusal means exclusion. This takes the form of rations withheld, welfare suspended and rights denied. The stability of systems depends on obligations never closing, only shifting forward.

Refusal within such systems is systematically delegitimised. A worker who rejects caste-coded labour is accused of dishonouring tradition. A family that resists repayment is branded delinquent. A community refusing resettlement after dam construction is framed as obstructing progress. Refusal is coded as betrayal, irrationality, even criminality. By stripping refusal of legitimacy, systems foreclose agency itself.

For futures practice, the task is not to romanticise escape but to expose where inheritances have been loaded with extraction and to design ways of unbinding. Futures work, if it is to matter here, must confront extraction as inheritance and not sidestep it.

Surfacing Inherited Futures for Re-imagination

Now, if inheritances weigh so heavily on South Asian futures, the task of futures work is not to ignore them, but to surface them as active ground. Futures are composed in the midst of residues, constraints, and obligations already in motion. To work with inheritances means to find ways of recognising them without romanticising, re-signifying them without assimilation, and redirecting them toward different ends.

This grammar is not written for communities already living with inheritances. It is written for us, “futures practitioners”, who are privileged enough to name ourselves as such, to do this work as practice and livelihood. The reminder here is that our task is not to prescribe escape, but to reconfigure how we engage with obligations and residues that are already shaping tomorrow.

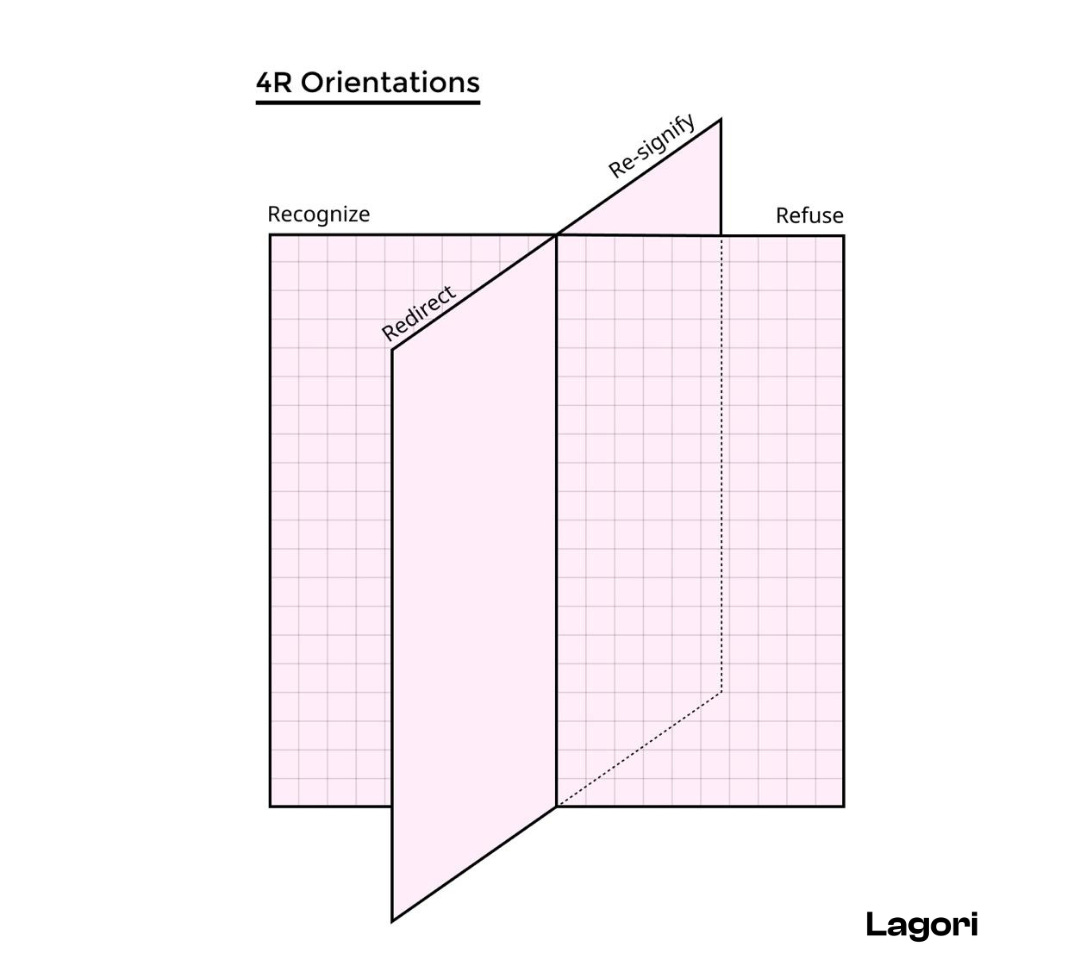

We call this the 4R Orientations

Recognize → Re-signify → Refuse → Redirect

Recognise

The first orientation is to see inheritances as live conditions. Recognition is a practice of naming what has been naturalised as “normal” and refusing to let it disappear into the background. To recognise is to surface these inheritances as constructed legacies. Without recognition, neither refusal nor redirection is possible and if that doesn’t happen, we cannot reshape what remains unseen.

In practice: What if we begin any futures inquiry by surfacing what is still active: debts, case files, infrastructures, before imagining what could come next?

Re-signify

The second orientation is to reinterpret inheritances without collapsing into assimilation. Practices, obligations, or identities can be opened to new meaning, reframed so they move differently. What was once coded as duty might be reframed as collective bargaining and what was once a stigma might become a source of solidarity. Re-signification does not erase the past, but unsettles the terms through which it governs, allowing inherited forms to circulate with altered force.

In practice: What if futures processes included exercises of re-signification, asking how rituals, roles, or labels might be re-read in ways that affirm dignity and expand possibility?

Refuse

The third orientation insists on legitimising refusal. To re-imagine futures is also to recognise that inherited conditions need not be carried forward unquestioned. Refusal here, is the act of surfacing what has been passed down and choosing not to continue it. To surface debt, caste labour, or ecological liabilities mistaken for destiny and to refuse their continuation, is to mark the limits of what should be inherited, and to open space for other arrangements of value, care, and belonging.

In practice: What if we build futures processes that explicitly allow refusal as an outcome, rather than treating it as a failure of participation?

Redirect

The final orientation is to move inherited conditions onto altered trajectories. Redirecting here, means shifting how these conditions flows forward. It asks: what can be bent, repurposed, or carried differently.

In practice: What if we prototype how inherited constraints, a registry, a loan, a ritual, can be bent toward collective ends rather than private burdens?

Together, these orientations provide a way of working with inheritances that neither denies their weight nor surrenders to it. They create a practice of futures grounded in what is already given, but refusing to let the given be the limit.

Carrying Forward, Differently

Rīn and Riyāz sit together as two grammars of continuity. One sets the coordinates: binding, insistent, already drawn. The other sustains rhythms: adaptive, practiced, chosen. Between them lies the space where futures take shape, moving inside coordinates while shifting rhythms, altering direction without pretending to start from nowhere.

South Asia sharpens this truth, but it is not unique to it. Everywhere, futures are shaped less by blank choice and more by what systems, ecologies, and lineages already placed in hand. The question is whether these inheritances are surfaced as conditions or erased in favour of fantasies of rupture. To work from inheritance is to admit that no future begins clean.

The provocation here is not only for South Asia but for global futures practice: stop imagining escape routes, start designing re-directions. Treat refusal as legitimacy, fragments as live matter, entanglement as ground. These are materials for imagination.

What matters is not to deny inheritance, but to reconfigure it, so that liability becomes shared obligation, silence becomes ground for voice, and repetition becomes rhythm otherwise rehearsed.

This essay is part of Lagori Collective’s South Asian Futures framework, an inquiry that stays with loaded inheritances, situated continuities, and the fragile work of carrying futures differently. It asks how futures are not only rehearsed but also inherited, how systems embed their own afterlives, and how agency emerges in the act of insertion rather than escape.

If these notes resonate, we invite you to carry them forward with care in how they are critiqued, reimagined or cited. We see this as a way to amplify voices from the region, and to remind futures practice that no thought stands alone.

Suggested citation:

Kothari, D. & Mutaher, A. (2025). Rīn (ऋण): Inheritance as Futures Already Owed. Notes From In Between, Lagori Collective.

Dhaval Kothari and Alifiya Mutaher are design researchers, strategists, and co-founders of Lagori Collective. Lagori is an interdisciplinary research and design lab based in India working across South Asia. Grounded in research and participatory approaches, Lagori advances futures thinking through collaborative projects, research, programming, and strategic foresight. At its core, Lagori is building imagination infrastructure in the region by reshaping systems and expanding collective capacity, while ensuring that futures thinking is not abstract but rooted, situated, and durable.

Notes From In Between is a record of our in-progress thinking, provocations, open questions, and ongoing experiments at Lagori’s Social Design Lab. It’s where we make our process public, not to present answers, but to invite conversation. Check out our previous Notes From In Between - Mausam, Jivrut, Beejaya, Teh, Kal, and Riyaz.